Implications From UK’s Decision to Exit ICE by 2035

The UK government recently announced a plan to bring forward a complete ban on UK sales of petrol and diesel engine vehicles to 2035 from 2040. The decision was made in response to experts who said that 2040 was too late for the ban if the UK wanted to achieve its target of becoming net-zero by 2050. Contrary to industry expectations, the government is now including Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV) and Plug-in Hybrids Electric Vehicle (PHEV) in the ban. As cars are typically on UK roads for 14-15 years, a ban had to happen by 2035 to rid polluting vehicles from the road in time for net-zero emissions target of 2050.

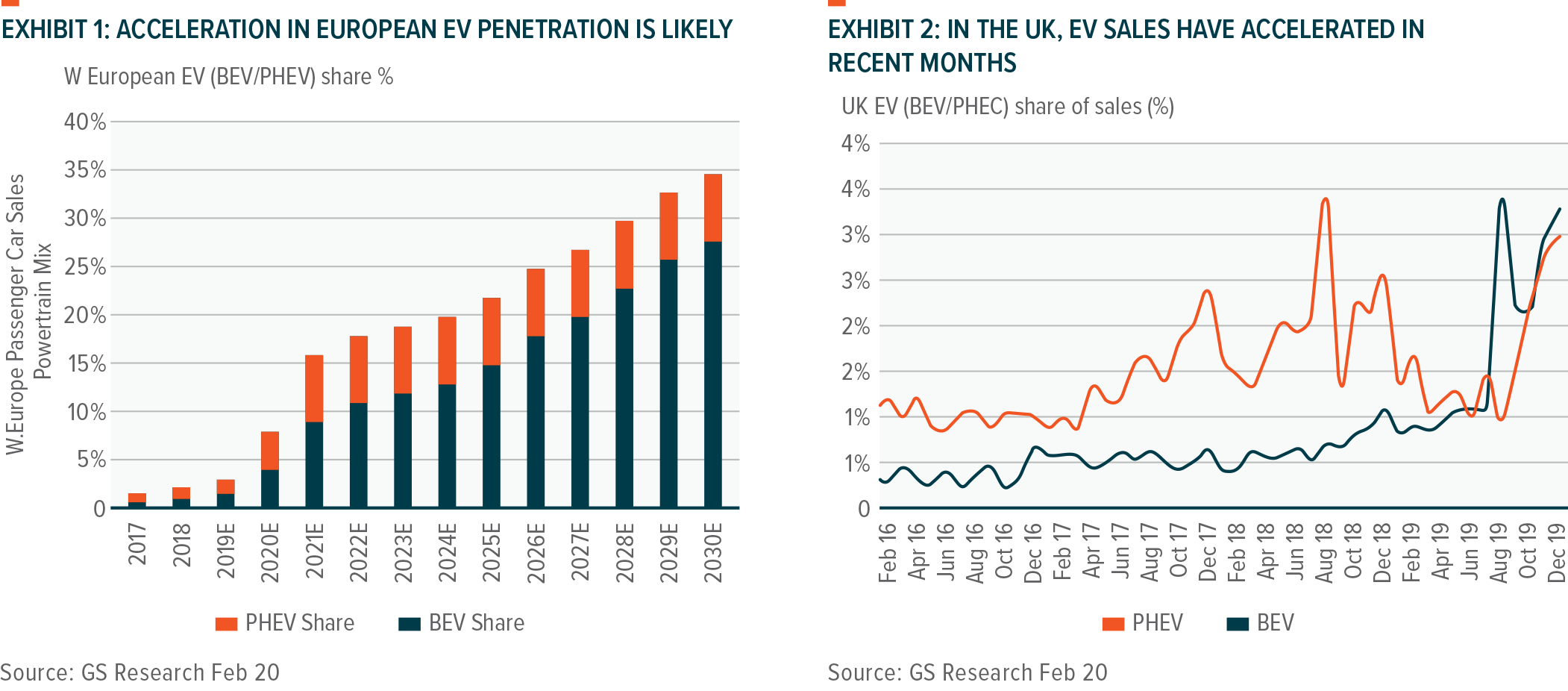

We believe the target to be exceedingly ambitious given the short period of time (less than two vehicle cycles; provided the vehicle development lead times are typically five years, and the subsequent life is 6-7 years) in addition to the current lack of charging infrastructure. To combat this, legal measures are being taken to create an open-access network of charging stations. 2035 regulations need to be taken into consideration by Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) for their planning of next-generation products in the subsequent 1-2 years. The proposal is reportedly suggesting a stop-sale as opposed to a ban on vehicle usage by 2035. In the UK, currently, less than 3% of cars sold are Electric vehicle (EV), with Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) only accounting for 1% of all cars sold. This would entail going from 1% to 100% in 15 years1. The situation will likely be exacerbated by Brexit, with imports into the UK likely to be more expensive than before due to tariffs. At the same time, the cost of making cars in the UK will also increase due to higher prices of imported auto components. To encourage the take-up of EVs and shorten waiting times for new vehicles, we think the UK government might encourage more direct OEM investment into UK-based supply chains such as battery giga-factories.

This latest proposal by the UK government seems more aggressive than what OEMs are projecting, mainly if PHEVs are included in the ban. Moreover, using the UK as an example, it would appear that the timeline is accelerating. The same could possibly happen in the EU. We believe that OEMs would no doubt have higher cost pressure as they plan for this expedited timeline, while the transition from ICE to BEVs would be even more painful than previously expected.

Among the OEMs, Volkswagen has a lead in terms of an expedited EV timeline. While most OEMs have BEV products in the market with plans to launch more in coming quarters, the level of VW’s spend (€33bn planned over five years) and ongoing strategy (2 dedicated BEV platforms, eight dedicated MEB plants, 70+ new models by 2028) should mean the company is well-placed to capitalise2. BMW’s BEV roll-out is less transparent than others, with only the MINI BEV, the iX3, i4, and iNext highlighted for launch. BMW continues to develop its BEVs on combined ICE/BEV platforms that are unlikely to maximize range and battery efficiency. The current specifications of the new electric MINI, 32.6kWh battery, and a 140-mile range is 35% less than the range of VW’s ID3.

In conclusion, while we believe in the direction and shift away from ICE cars, the faster than expected pace of regulation is expected to weigh heavily on the profitability of global OEMs.